Research

A regularly updated summary of my publications, working papers, and research goals.

Publications

Was Washington’s First Term Legitimate?: Texas v. White and the Constitutional Convention

When scholars and professors of constitutional law recount the origins of the Union, two conflicting theoretical accounts are often presented. In the first theory, the Constitutional Convention of 1787 was convened, as the Founders presented at the time, under the authority of the Articles of Confederation, with the Constitution created under the authority to amend the Articles. In the alternate theory, the Articles were scrapped altogether, and the Convention proceeded of its own will, with the Constitution emerging as an artifact of political realism. In a landmark Reconstruction Era case, Texas v. White, Justice Salmon P. Chase adopted the former view, in which the Articles are seen as preserved, forming a backbone of continuity stretching forth from the time of their adoption. This article traces the logical implications of these theories, concluding that the Articles of Confederation’s unanimity requirement combined with two states' late ratifications of the Constitution would, under Justice Chase's preferred theory, render George Washington’s first term as president, and any legislation it produced, a nullity. Ironically, it concludes, the safer and more conservative theory is one in which the Constitutional Convention is understood as an ultra vires act by the Framers, rebelling first against the English Crown and, second, against themselves.

To Sever or Not to Sever: Mixed Guidance from the Roberts Court

In its 2019-2020 term, the Supreme Court attempted to clarify its severability jurisprudence in two cases: Seila Law LLC v. Consumer Financial Protection Bureau and Barr v. American Association of Political Consultants. This essay argues that these opinions by Chief Justice Roberts and Justice Kavanaugh only further muddied the waters on severability, sending inconsistent signals as to the role of legislative intent in severability decisions. On the other hand, the competing theory of Justices Thomas and Gorsuch is clearer in its guidance but might lack the historical support that its advocates claim. The result, after much spilled ink, is a failure to move the needle on how the Court will handle an important question of statutory interpretation going forward.

Declared War and American Victory: A Search for Effective Commitment

Over the last seventy years, the United States has abandoned its longstanding practice of formally declaring war. It has also seen a dramatic decrease in the success of its military efforts over this period. This paper posits a link between the two, viewing declarations as a commitment device that links legislators' reputations to the outcomes of wars. British Journal of American Legal Studies, vol. 9, no. 2 (2020)

Supermajorities: A Proposal for the Judiciary Evaluated

In a 1984 article in the Journal of Legal Studies, Gordon Tullock and I.J. Good proposed a reform to the American judiciary that would have raised the threshold number of appellate jurists needed for a decision to become binding on lower courts, increased the number of cases that the Supreme Court hears, and prolonged the wait time for “good,” highly durable precedent. Recognizing the trade-off between timeliness and best results, Tullock and Good proposed still longer delays in exchange for even better results. This paper looks to the record of appellate decision making since that time to determine the proposal’s projected impact on precedent creation and costs to the legal system. Further arguments for and against the proposal are weighed in light of these findings. [Forthcoming in the Journal of Law, Economics, and Policy]

Working Papers

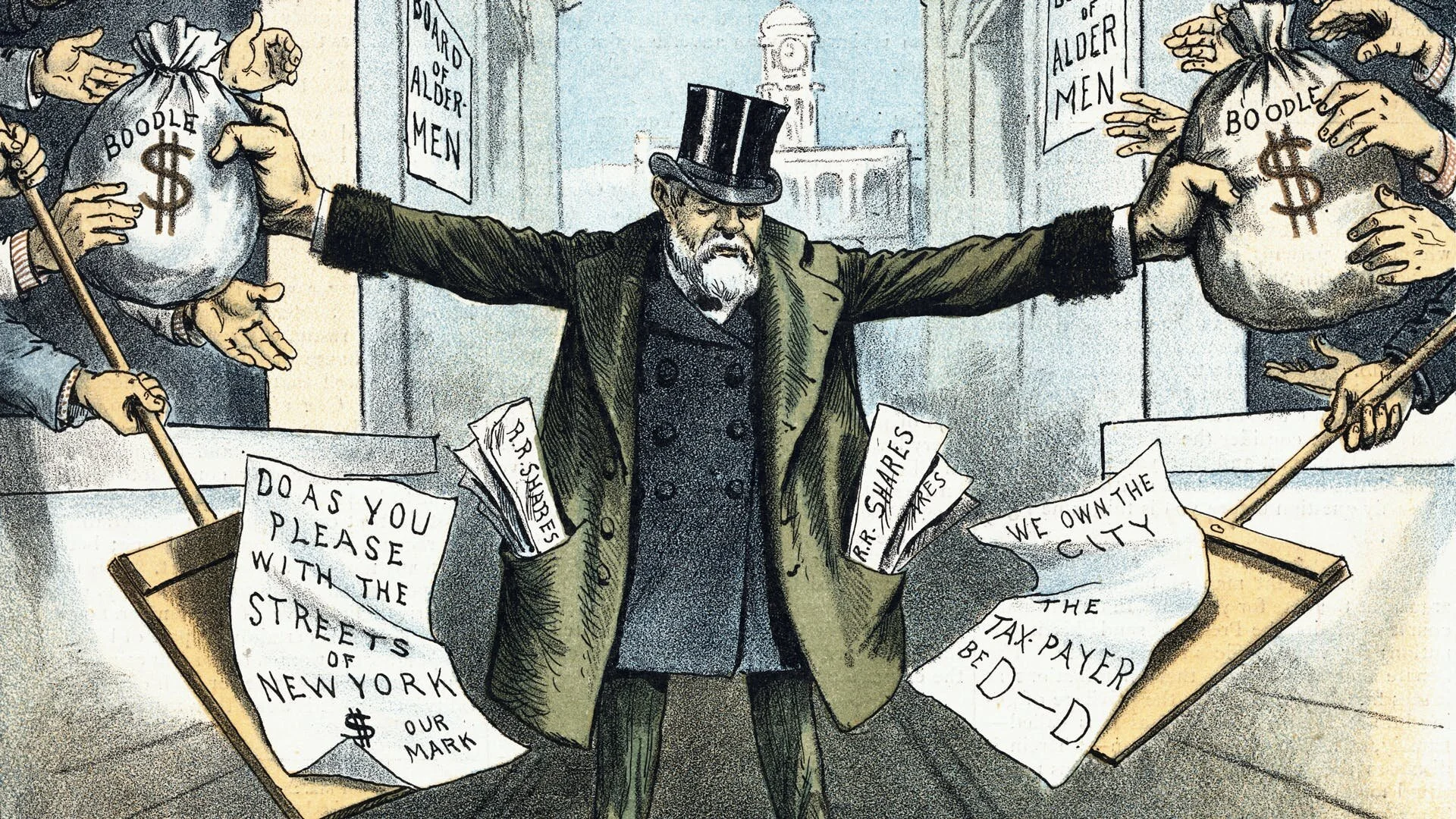

A Theory of Special Legislation and Its Decline

For most of a millennium, “legislation” largely meant special legislation: narrow bills tailored to the interests of particular persons, firms, or property. Generally applicable acts that covered all persons were greeted with suspicion. Today, the reverse is true: experts and the public believe that laws, to be good, must be broad and have largely abolished special legislation. This article frames both special legislation and its abolition as efficient solutions under alternate institutional constraints. It argues that scholars have failed to recognize the substitute nature of special legislation and the administrative state and finds criticisms of special legislation to be attenuated when subjected to comparative institutional analysis. Finally, it argues that rent-extraction during the American transportation boom was the immediate impetus for the shift.

Scandal

Despite its salience in modern politics, political scandal has yet to be treated as a subject of inquiry in political economy. This paper offers a rational choice theory of scandal as the result of the strategic production and use of scarce knowledge regarding politicians, parties, and organizations. It argues that given voters’ limited memories and politicians’ desire to maximize votes, scandalous information will be an object of speculative investment, produced and stored in order to maximize its political profits via optimally timed release to the public. The incentives of parties and campaigns in both primaries and general elections are considered, and evidence is examined on the coincidence of scandal and election seasons.treated as a subject of inquiry in political economy. This paper offers a rational choice theory of scandal as the result of the strategic production and use of scarce knowledge regarding politicians, parties, and organizations. It argues that given voters’ limited memories and politicians’ desire to maximize votes, scandalous information will be an object of speculative investment, produced and stored in order to maximize its political profits via optimally timed release to the public. The incentives of parties and campaigns in both primaries and general elections are considered, and evidence is examined on the coincidence of scandal and election seasons.

Presidential Nomination and the Birth of Executive Federalism

In 1968, the Democratic Party changed its method of nominating presidential candidates from the convention floor system to the primary system. In 1972, the Republican Party followed suit. In the interim, under the banner of “New Federalism,” President Nixon introduced the block grant system and federal revenue sharing programs by which the executive could more directly execute transfers to the states without congressional interference. This paper argues that this expansion of “presidential pork-barrel” constitutes a spoils system by which presidential candidates could more directly lobby state politicians for support in the new primary system.

Is There a Public Choice Theory of the Great Recession?

Anderson, Shughart, and Tollison's 1988 paper "A Public Choice Theory of the Great Contraction" provided significant evidence countering the Friedman-Schwartz (1963) "mistake theory" of the 1929 Great Contraction, introducing an interpretation of that episode as created by political and bureaucratic incentives to support Fed member banks at the expense of non-member banks. In studies of the 2007-2009 Great Recession, however, mistake theories have again assumed the forefront of analysis. Challenging that approach, this paper applies an analogous test to the Great Recession, using panel data to determine whether the same process found by Anderson, Shughart, and Tollison can be said to have occurred in that episode.

Conditional vs. Unconditional Surrender: An Economic Perspective

In conflict and peace studies, the political preference for conditional surrenders as a merciful means of resolving warfare goes back at least a century. This paper contends that, contrary to its appearances of mercy, a general tendency exists in the history of warfare for conditional surrenders to lead to prolonged and recurrent conflict between two combatants and for unconditional surrenders to precede lasting peace. This phenomenon is explained by framing surrenders as contracts which, to be effective, must correspond to the property and relative strengths of combatants.

The Role of Moral Hazard in the Housing Boom and Bust

Considerable talk has been heard as to the role of moral hazard in the 2007-2008 American housing bust, but to date no paper has thoroughly explored the nature of its workings and the role that policy played in fostering moral hazard. This paper sets out to fill that void.

Commercial Bank Competition, Riegle-Neal, and Dodd-Frank

This paper uses a linear systems of equations approach to model and test the effects of two major pieces of legislation, one a significant regulation and the other a major deregulation, on the degree of monopoly power in the U.S. banking market over the period 1984-2016.

Strategic Considerations of Monetary Policy in Civil War

What happens to the currency when a nation is divided in half by civil war? What strategic considerations influence secessionists' choice of whether to keep their old currency or create a new one? Can currency manipulation be used as a strategic weapon in this context? This paper offers a primer on such questions.

Crises as Precursors to the Foundings of Central Banks

The notion that currency suffered either from market failure or inherent instability before central banks has been thoroughly challenged by existing literature. As this paper notes, however, many major central banks did emerge in times of crisis. Were these benevolent attempts at stabilization or political opportunism?